Europa is one of Jupiter’s largest moons. Discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei, Europa has changed the way we view the cosmos. It showed unquestionably that the Earth was not the centre of all motion in the universe. Beneath its icy shell lies a vast, hidden ocean that may even harbor life. But how do we know that Europa has an ocean if we’ve never drilled through its thick ice? Scientists rely on several lines of evidence, including data from spacecraft, observations of surface features, and magnetic field measurements.

Galileo’s Magnetic Field Measurements

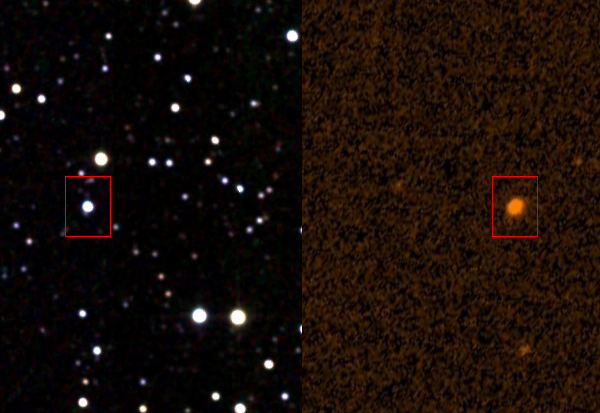

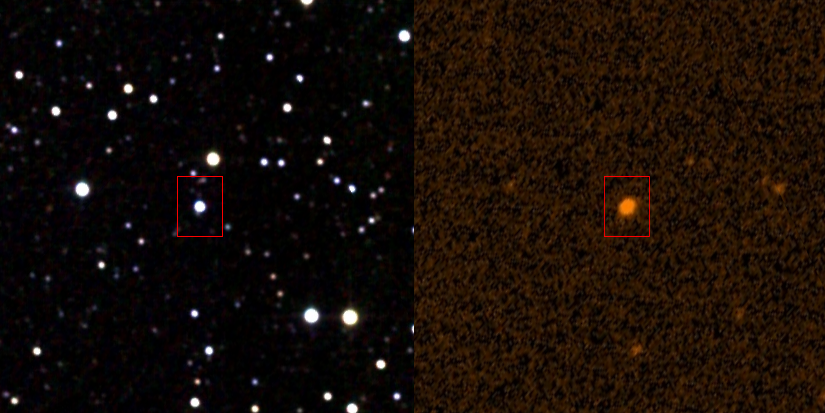

One of the strongest pieces of evidence for Europa’s ocean comes from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003. Galileo’s magnetometer detected a changing magnetic field around Europa. This variation suggested the presence of a conducting layer beneath the surface—most likely a salty, liquid ocean.

Since Europa moves through Jupiter’s strong magnetic field, an electrically conductive ocean would generate an induced magnetic field in response to this movement. Galileo’s data showed exactly that, providing compelling evidence of a global, subsurface ocean.

Surface Features and Ice Dynamics

Europa’s surface is covered in a network of cracks, ridges, and chaotic terrains—evidence that the ice is constantly shifting. These features suggest the presence of a liquid layer beneath the surface that allows the ice to move.

Some key observations include:

- Ice Rafts: Some regions of Europa resemble icebergs that have broken apart and drifted before refreezing. This suggests a floating ice shell with liquid water below.

- Double Ridges: Europa’s surface is crisscrossed by double ridges, which resemble features seen in Earth’s ice sheets over water pockets. Recent studies suggest these ridges form due to water pushing upward from below.

- Surface Age: Europa’s surface appears geologically young, with few impact craters. This suggests continuous resurfacing, likely caused by upwelling from an underlying ocean.

Never Miss A Story

Plumes of Water Vapor

In recent years, the Hubble Space Telescope and other instruments have detected plumes of water vapor erupting from Europa’s surface. These geysers likely originate from cracks in the ice, similar to those seen on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

The presence of these plumes suggests that Europa’s ocean is not only there but also interacting with the surface, potentially making it easier to study without drilling. NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission will investigate these plumes to learn more about their composition and what they reveal about the ocean below.

Tidal Heating and Internal Energy

Europa orbits Jupiter in a slightly elliptical path, causing strong gravitational interactions. This results in tidal flexing, where the moon’s interior is stretched and compressed, generating heat.

Tidal heating is crucial because it prevents the ocean from freezing solid. Even though Europa is far from the Sun, this internal energy source keeps the water liquid beneath the ice. Computer models show that Europa likely has enough heat to maintain a subsurface ocean for billions of years.

Conclusion

Although no spacecraft has directly accessed Europa’s ocean, the combined evidence from magnetic field measurements, surface geology, water plumes, and tidal heating makes a strong case for its existence. Future missions like Europa Clipper will provide even more insights, potentially answering one of the biggest questions in planetary science: Could Europa’s ocean harbor life?

With its salty water, energy sources, and possible chemical interactions, Europa remains one of the best places in our solar system to search for extraterrestrial life.